Article

10 min read

Open Banking in Europe has steadily moved on from “getting PSD2 right.” Under PSD2, the XS2A rule required banks to give licensed third parties regulated access to account data through basic APIs. That requirement has been met across most of the market. Now, PSD3 and the proposed Payment Services Regulation (PSR) focus on how these APIs work in real conditions. This means reliable uptime, clear documentation, and clear responsibility when incidents occur.

In Eastern Europe, legacy core banking systems and vendor-controlled API layers limit how quickly banks can adapt. As a result, Open Banking is not a one-off regulatory exercise. It requires long-term changes to system design, integration, and ownership.

TL;DR (Key Insights):

Open Banking is moving from following the rules set by PSD2 to a system that puts APIs first, to facilitate instant payments and enhance the integration with third-party systems.

PSD3 and the Payment Services Regulation increase expectations for API uptime, documentation, liability, and consistent SCA across channels.

Moldova and Romania follow the same European rules, but they have different levels of API maturity, infrastructure readiness, and adoption speed.

Bank system architecture has become a decisive factor in whether institutions can reliably support SEPA Instant, A2A payments, and modern identity flows.

What open banking means? (in EU context)

Open Banking is not a product or a single regulation. It is a mechanism that defines how financial data and payment initiation can be shared securely between banks and licensed third parties, with the customer in control. In Europe, this model exists to increase competition, enable new financial services, and reduce reliance on closed, bank-only systems. Regulation defines how it works, but the value of the concept comes first.

What PSD2 introduced in practice

PSD2 introduced three structural changes that enabled Open Banking in practice:

defined XS2A, allowing licensed third parties to access account data and initiate payments via APIs

created regulated AISP and PISP roles, establishing a formal framework for third-party providers.

enforced Strong Customer Authentication (SCA) for secure logins and payment initiation.

This broke the “only the bank sees your data” model. But the EBA notes that, because there is no single EU API standard, banks implemented XS2A differently, leading to unstable, inconsistent interfaces. (everyone built a PSD2 API, none of them behave the same.)

As a result, modern banks increasingly treat Open Banking as a platform question. This means using API gateways for routing and logging, OAuth2-based consent so customers explicitly approve access, and SCA patterns that preserve a smooth mobile experience.

PSD3 and the Payment Services Regulation

PSD3 and the new PSR go beyond requiring banks to “have an API”. They define how those APIs must operate in real-world conditions. That means they push for 99%+ uptime, clearer fraud liability, stronger SCA rules, and better documentation.

Because PSR is a regulation rather than a directive, it applies directly across the EU and raises the minimum operational standard for all banks. (version 2 was “build it”, version 3 is “make it reliable and safe enough for real products”.)

Open Finance "the next stage of data sharing"

Open Finance extends the principles of Open Banking beyond payments and current accounts to other financial products, including mortgages, pensions, insurance, and investments. The underlying model remains the same: standardized, customer-consented data sharing between institutions.

In the UK and the EU, initiatives such as the planned Financial Data Access regulation (FiDA) are testing how this model could work in practice, with early timelines pointing toward the second half of the decade. Once PSD2 and PSD3 stabilise, banks are expected to move away from one-off compliance projects toward a continuous API roadmap that supports broader data-sharing use cases across the balance sheet.

How open banking works? (at a technical level)

Open Banking is not a single interface or product. It is a layered technical model designed to allow secure third-party access without exposing the core banking system directly.

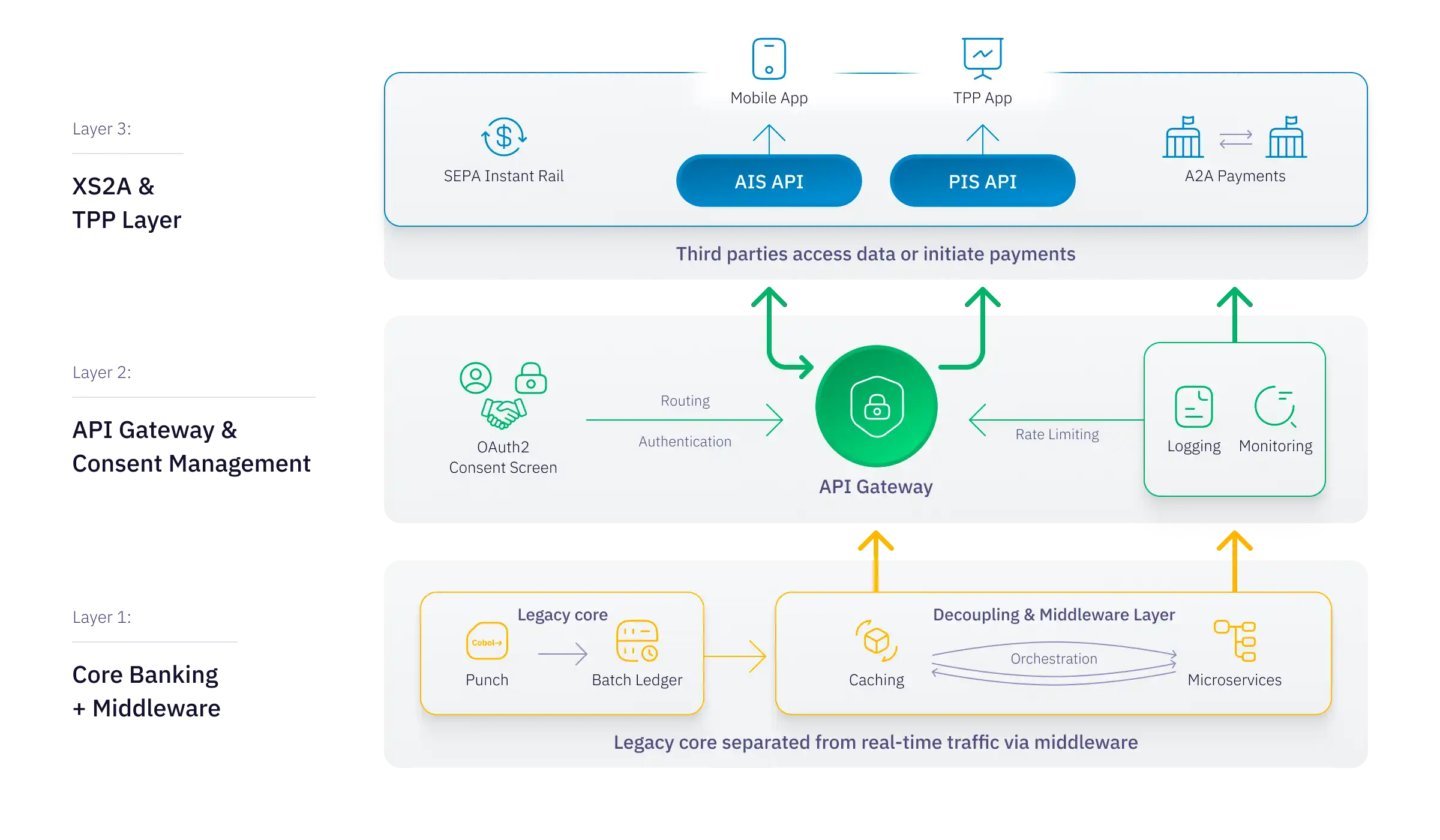

In practice, it relies on three interconnected components: an API gateway with consent management, standardized XS2A interfaces, and a decoupling layer that separates real-time traffic from legacy core systems.

API gateways and consent management

API gateways act as the controlled entry point between banks and third-party providers. They authenticate incoming requests, enforce rate limits, and log all interactions for audit and regulatory compliance. This layer ensures that external access is secure, traceable, and governed by policy rather than direct system exposure.

On top of the gateway, OAuth2-based consent management allows customers to explicitly approve access to their accounts. Users decide which data can be accessed, for what purpose, and for how long. In practical terms, this replaces background data scraping with a clear, auditable “yes or no” decision made by the customer.

XS2A and TPP experience

XS2A (Access to Account) defines the rules and interfaces that AISPs and PISPs use to retrieve account information or initiate payments. Some banks achieve this through their own API platforms; others accelerate compliance via vendor-managed gateways that bundle connectivity, consent handling, and security into an external service.

On paper, both count as “Open Banking.” In reality, TPP adoption is driven by behaviour: stable OAuth2 redirects (no broken loops), predictable error codes, and solid uptime. If each bank behaves differently, even through the same vendor, ecosystem growth slows down. Fintechs will not invest in integrating 10 times with 10 subtly different APIs.

Legacy cores (middleware & decoupling layers)

Most banks in the region still rely on legacy cores tracing back to 1960s mainframe-era systems designed for batch processing (e.g., COBOL-based ledgers handling end-of-day reconciliations). Even when digital interfaces appeared in the 1980s–1990s, they mainly added screens on top of the same monolithic engine.

Middleware naturally emerged as a bridge, providing a layer that caches frequent reads, orchestrates calls, and exposes small, reusable services (microservices) to the outside world. Over time, this evolved into a decoupled architecture with layers forming a 'parallel shell', allowing the core to focus on accounting while the outer layer handles real-time demands.

(Decoded: In other words, the old engine still runs the car. However, a modern transmission and control system enables it to be driven on a highway of APIs. Not a country road of evening batches.)

SEPA Instant and A2A Payments

SEPA Instant (EU’s 10s payment system)

SEPA Instant enables euro transfers to be settled in under 10 seconds, 24/7. There is no such thing as a "we'll book this tomorrow morning" option, money have to be transferred between banks instantaneously. Under the EU Instant Payments Regulation, banks must already be able to receive instant payments, and they will gradually be required to send them, too. This will force everyone to use real-time systems.

For businesses, this eliminates settlement delays and facilitates transactions where account-to-account transfers become the norm.

A2A payments (the economy engine behind)

Account-to-account (A2A) payments enable money to move directly between bank accounts without card intermediaries. As instant-payment rails mature and PSD2/XS2A interfaces stabilize, A2A becomes the most financially meaningful Open Banking use case for banks.

The BCG “Reimagining the Future of Finance” report (2023) shows that Europe’s fintech revenues are expected to grow from $42Bn in 2022 to $190Bn by 2030, a 21% increase driven largely by account-based payment models and real-time settlement infrastructure.

For banks, the implication is clear: once XS2A is stable and SEPA Instant becomes the norm, A2A stops being “an alternative method” and becomes a core revenue driver, enabling cheaper euro transfers, automated payouts, and new embedded-finance products.

Moldova and Romania (2 different starting points)

Moldova and Romania operate under the same broad European rules but face different constraints and timing.

Moldova’s roadmap (BNM’s early-stage alignment)

Moldova’s modernisation path has two big milestones: PSD2 alignment and SEPA accession. In December 2023, the European Payments Council accepted Moldova into the Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA), and by 2024 the country was connected to SEPA Credit Transfer and SEPA Instant — so euro payments can now follow the same fast, low-cost rules used in the EU.

At the same time, domestic behaviour is changing: card-based payments grew by 20% year-over-year in 2023, a clear signal that consumers are comfortable paying digitally. The weak link is the API layer. Banks sit at very different stages of PSD2 implementation, some using vendor gateways, others just starting to expose XS2A interfaces. BNM’s agenda now is less about “joining SEPA” and more about raising API quality and authentication flows so those new rails can actually support real-time, API-based products.

(Decoded: people are ready, the rails are ready, the backend still needs to catch up.)

Romania’s adoption (BNR, SEPA Instant, aggregators)

Romania moved earlier on PSD2, transposing it into local law and putting the National Bank of Romania in charge of supervising banks, payment institutions, and licensed fintechs. According to Open Banking Tracker, 15 banks and account providers expose 52 PSD2 APIs — a solid foundation for AIS and PIS use cases.

At the same time, BR’s interview with BNR notes only two locally licensed TPPs. This remains a small number compared to the potential market size (19 million people and 76% banked adults), which gives many banks reason to continue relying on vendor-managed XS2A gateways.

The next stage for Romanian banks is less about “having an API” and more about owning the API stack—controlling performance, SCA patterns, and rollout of new products instead of outsourcing those decisions to a third party.

Why banks find open banking difficult?

Two structural issues keep showing up across the region: heavy reliance on vendor proxies and the limits of legacy cores.

Vendor proxies vs. owning your API platform

XS2A vendor gateways help banks to meet PSD2 deadlines quickly and with less internal effort. They combine compliance, security and connectivity in a single product. However, this comes at the cost of flexibility. Upgrade cycles depend on the vendor rather than the bank, errors and edge cases are more difficult to resolve, and TPPs often experience inconsistent behaviour across institutions, even when they use the same provider.

Consequently, more mature banks are gradually transitioning to hybrid or fully internal gateways. While vendor proxies remain useful as accelerators, long-term control over performance, security and developer experience tends to be more effective when managed in-house.

Legacy cores block real-time banking

Legacy cores are effective for batch-based payment cycles, but encounter difficulties with ongoing API traffic and 10-second settlement requirements. While middleware can mitigate some of these issues through caching and orchestrating calls, it cannot transform a batch engine into a real-time platform independently.

The longer-term solution is decoupling. This means isolating the core behind a stable API contract. Then a modern, event-driven layer can handle real-time demands.

(Decoded: If every new product hits the core directly, it'll put a limit on the company's ability to create new things.)

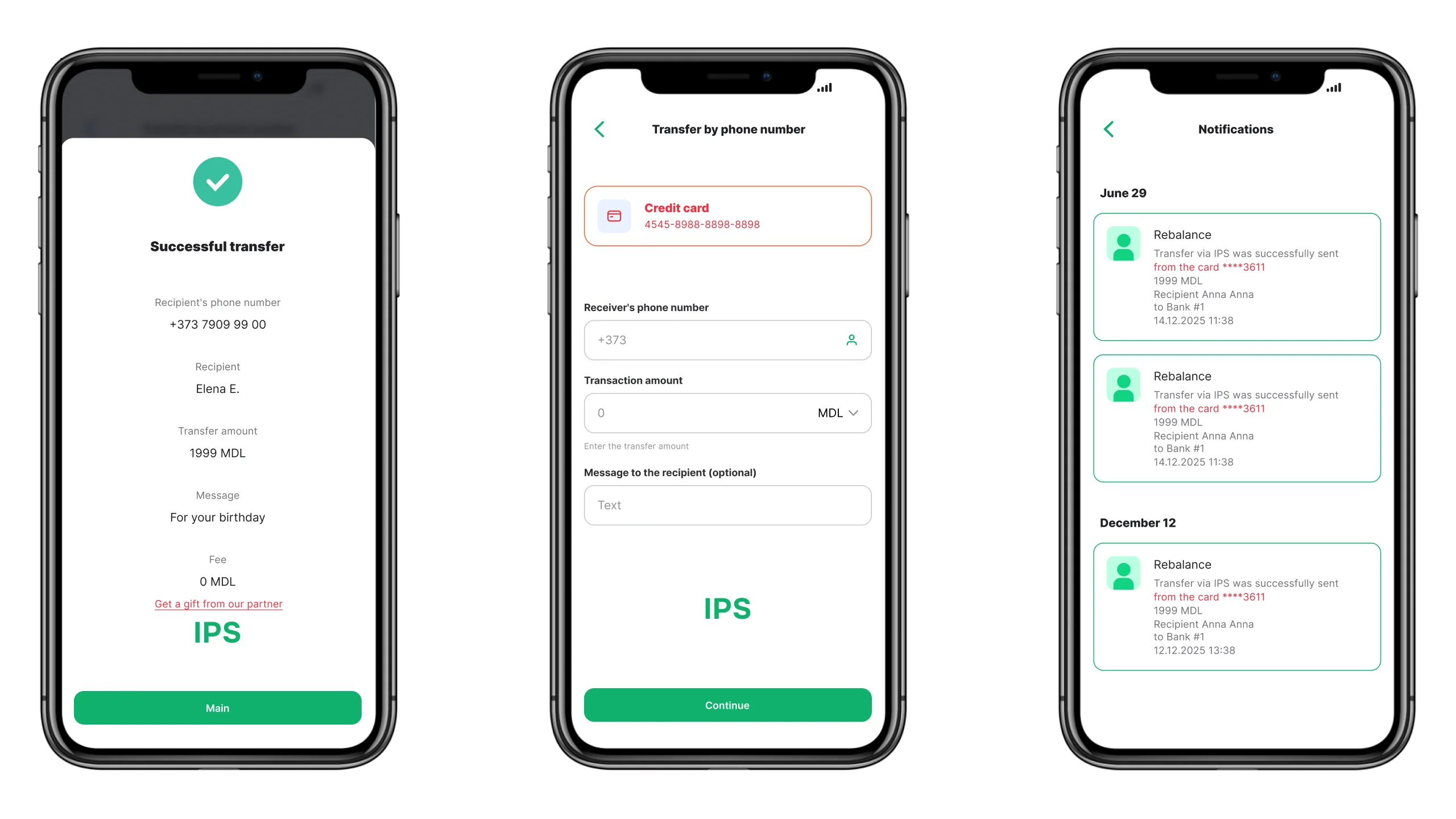

Modernizing PSD2 & IPS (our experience)

We have covered a similar pattern of structural constraints with a bank from Eastern Europe in a PSD2 and IPS compliance case. PSD2 compliance deadlines, the integration of Instant Payments, and an existing mobile app all collided with a legacy core that could not handle real-time API traffic.

Rather than replacing the core, we:

introduced a decoupling layer to absorb API spikes and coordinate calls;

unified SCA logic across channels;

rebuilt the mobile app around a modular, API-first design.

(decoded: the old system kept doing accounting, while real-time execution moved outside it.)

The result was an increase in monthly transactions from around 27,000 to 600,000, over 300,000 active users, transfers executed in under one second, and full PSD2 + IPS compliance ahead of schedule. That’s what 'API-first' really looks like in practice.

What should banks prioritize next (in plain language)

Five priorities stand out for banks in Eastern Europe that want to set themselves up for growth:

build a decoupling layer so that APIs do not overload the core;

unify SCA and identity across mobile, web and TPP flows;

stabilise XS2A behaviour so that third parties can integrate once and rely on it;

prepare early for PSD3 and PSR rather than waiting for a new compliance crisis;

treat APIs as infrastructure, not a by-product of regulation.

Banks that follow this approach will integrate faster, launch products sooner and avoid adding new technical debt to existing systems. Those that remain in 'minimum viable compliance' mode will see the gap widen as instant payments, A2A flows and Open Finance data-sharing models become the new normal.

If you plan similar transformations, our work in financial technology and banking systems outlines how these architectural principles are applied in practice.

Share this article on:

More insights

Article

Finance & Banking

Digital Transformation

10 min read

Banking process automation enables financial institutions to replace manual approvals with low-code workflows that integrate payments, lending, and compliance in real-time. It ensures PSD2 and KYC/AML compliance while enabling instant payments, such as SEPA Instant and Moldova's IPS, for faster and safer banking.

11 Nov 2025

Article

IT Consulting

Business Analysis

Digital Transformation

6 min read

Learn how consulting has changed—and why it works better than traditional approaches. *Real examples from our porfolio included - showing how it solves problems others couldn’t.

22 Apr 2025